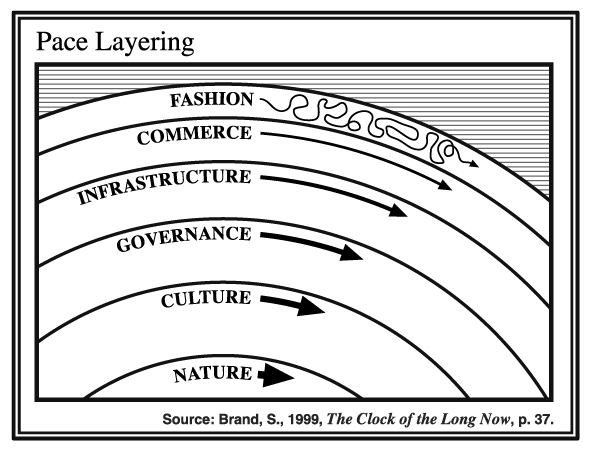

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about Stewart Brand’s concept of pace layering, which offers a compelling way to understand the different layers within systems and how they change at varying speeds. It’s a powerful idea, especially when we consider the bigger projects we’re sometimes involved in, particularly those that aim to affect systemic change.

For those unfamiliar with Stewart Brand, he’s an influential thinker, writer, and environmentalist best known for his work on long-term thinking and systems change. Brand is perhaps most famous for creating The Whole Earth Catalog in the late 1960s, a publication that became an essential resource for the counterculture movement and early environmentalism. He also founded The Long Now Foundation, an organization dedicated to fostering long-term thinking in the context of global sustainability. Brand’s work spans a wide range of topics, from architecture and technology to biology and society, with his concept of pace layering originating in his book The Clock of the Long Now, where he explores how civilizations balance the fast and slow aspects of progress.

At its core, pace layering suggests that different systems—whether they be social, environmental, technological, or political—move at different rates. Fast layers innovate, while slow layers stabilize. Recognizing which systems are operating parallel to our own work and how they influence us is crucial. Each of these systems may change at a different pace. The key is to discern which layers are moving most slowly, which are changing more rapidly, and how we might interact with each of these layers differently based on their speed of change.

Understanding and Interacting with Layers

One of the most important aspects of this framework is understanding that some systems naturally move slowly. For example, Brand’s slowest layer is nature. While it evolves over millennia, it can occasionally leap through events like earthquakes or floods. But slowness is inherent to its nature.

In our work, we encounter systems that appear slow. However, their slowness isn’t necessarily part of their essence. Sometimes, they’re just resistant or hesitant to change, which is very different from being incapable of change. Conversely, we might see systems that seem to move fast, but we shouldn’t mistake that speed for a fundamental change in their nature. Like nature’s leaps, these fast movements can be temporary or reactionary, without altering the system’s core pace.

An Example: The Education System

Let’s consider the education system, which is often criticized for being slow to change. Curriculum reform, for instance, can take years to implement, and any changes tend to be incremental. This slow pace is often by design, meant to preserve stability, ensure broad consensus, and mitigate the risk of frequent disruption.

But the intentional slowness of the education system has led to growing dissatisfaction—interesting from both sides of the political spectrum. As a result, we’ve seen a rise in alternatives like homeschooling and micro-schools, where families bypass traditional education altogether. These newer models offer flexibility and adaptability, contrasting with the more rigid pace of mainstream education.

While the core system remains slow, this parallel layer of alternative education models has emerged at a much faster pace. It demonstrates that while the education system is designed to be cautious and methodical, there are parts of the ecosystem willing and able to move more quickly to meet evolving needs.

A Second Example: Urban Planning and Housing

Another relevant example is urban planning and housing development. In many cities, planning and zoning regulations are notoriously slow to change. These policies often serve as stabilizing forces, ensuring long-term growth is controlled and sustainable. However, this slowness sometimes clashes with more urgent needs, like housing affordability.

We’ve seen this recently in cities where affordable housing projects are stymied by bureaucratic red tape. In contrast, the rapid development of unregulated short-term rental markets (like Airbnb) is moving much faster than traditional housing development. This fast-moving layer disrupts existing regulations but doesn’t necessarily change the fundamental pace of the underlying system, which continues to operate slowly even in the face of new challenges.

Reflection

As you think about the work you do and the systems you engage with, consider: What systems are operating parallel to your work? Which ones seem to move quickly, and which are slower to adapt? More importantly, is their speed a fundamental part of their essence, or is it something that could change with the right conditions?

I invite you to reflect on your own experiences. What examples can you think of where a system’s pace—fast or slow—had a major impact on your work? Share your thoughts and let’s continue the conversation around how understanding these layers can lead to more effective strategies for change.