Like many organizations, Q1 started out a little slow for us – getting projects off the ground, getting our bearings after the holidays, and getting prepared for a busy year of impactful work. Our team decided to use this time to document and organize our process a bit more, finding ways to standardize some of the work we do and the methods we leverage to do it.

In reflecting on our work and getting organized, our team also sought to understand new approaches and theories to solving the design and social innovation challenges we face today. Design thinking and human-centered design have advanced innovation work significantly, but these methodologies alone are not enough to address an unprecedented world of new and increasingly complex challenges. We studied how other practitioners and firms talk about their approach to this type of work, and dug into critiques on design thinking as a practice. Before we could share our own approach, we felt it necessary to better comprehend the ways in which design can both solve for and worsen environmental and social justice issues.

“By embracing ‘design thinking,’ we attribute to design a kind of superior epistemology: a way of knowing, of “solving,” that is better than the old and local and blue-collar and municipal and unionized and customary ways. We bring in “design thinkers” — some of them designers by trade, many of them members of adjacent knowledge fields — to “empathize” with Kaiser hospital nurses, Gainesville city workers, church leaders, young mothers, and guerrilla fighters the world over. Often, as in Gainesville, the implicit goal is to elevate the class bases of the institutions that have organized their informants’ lives. Only within this new epistemology can such achievements be considered unambiguously good.”

Maggie Gram

‘On Design Thinking‘

This – combined with reflection on years of practice – culminated in the development of our own unique point of view, aiming to document and visualize our approach, while understanding and acknowledging the shortcomings of design thinking on the whole. As our practice continues to evolve, we will use a new framework to systematically communicate our approach externally to clients and collaborators, while also being able to consistently operationalize and manage the work internally.

The Importance of Framing

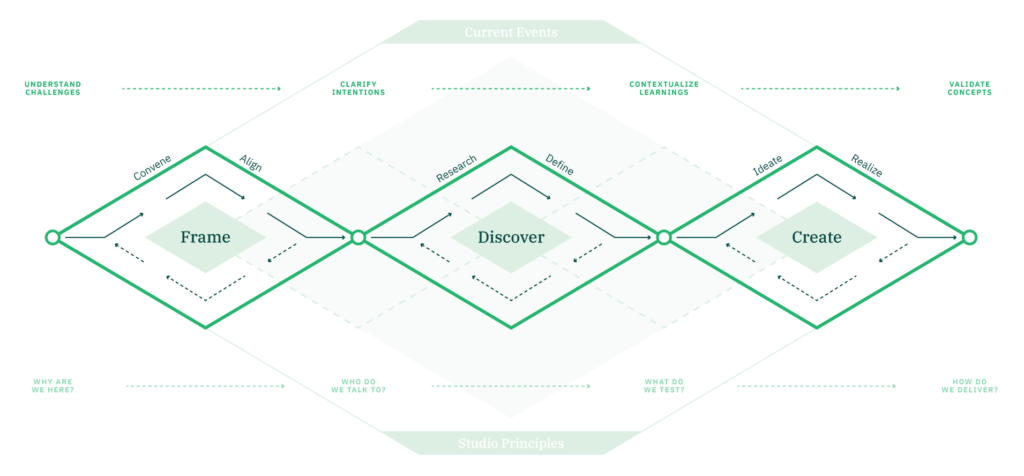

Throughout our efforts, we leverage a strong toolkit of design methods and processes to effectively frame challenges, discover opportunities, and create solutions. We noticed that conversations around design and innovation work often focus on discovery and creation, or in other words, researching a problem or opportunity and developing products or services that solve it. However, we have found that (arguably) the most important part of tackling complex design challenges happens up front, before any research or “design” actually takes place. When working with a client, we try to put a significant amount of effort into framing the challenge before we begin researching it and defining the problem or opportunity.

A Framework for Resilient Futures

During this reflection period, we realized that the emphasis on Framing in our work was only implicit to us, and not clearly explicit to our clients and the broader design community. This pushed us to modify the widely used double diamond, elevating Framing to be its own distinct phase and mode of work. Truly understanding an organization, the challenges it faces, and the broader implications for solving those challenges requires more than a workshop, a wall full of Post-It notes, and a glorified set of ambiguous design thinking questions. In order to clearly articulate a problem that is worth solving, we must convene different perspectives of an organization or community, then seek to align its stakeholders around intentions (not solutions) as a basis for defining the problem(s) at hand. We do not try to solve anything with an organization until there is clarity and alignment on why we’re doing what we’re doing — we find it is premature and costly to lean into solutionizing early on in the process before the challenge has been clearly framed. Taking time to fully comprehend the context of today will best support opportunities and strategies for a resilient future.

It’s this notion of a resilient future that we ultimately strive for with our clients—the state of thinking and acting where your organization can anticipate and respond to industry challenges, global disruptions, systemic inequality, and climate change. Framing, in this context, not only ensures we are working on the right problems, but also provides overall organizational direction. Clarifying this organizational intent and vision feeds problem solving and innovation.

We sometimes talk to our clients about getting all parts of their organization to “head west” together. Heading west does not provide a map and precise directions, but it does provide a focus for momentum building. West gets people talking about big goals. It orients them to other possibilities and doesn’t bog them down in tactics. Heading west frames what’s possible (Frame), stimulates our curiosity (Discover), and allows us to solve the real and right problems (Create).

If your organization is looking to build more resilience or simply head west, contact us.